CONDON’S

CORNER

The Value of “Invasive” Plants

[Published February 26, 2025, by The Daily Progress, the daily newspaper of Charlottesville, Virginia and The News Virginian, the daily newspaper of Waynesboro, Virginia]

https://dailyprogress.com/opinion/column/article_bd5a59a4-f3d7-11ef-9d44-dbecc45fb578.html

[Also published on March 17, 2025 by The Daily News-Record, the daily newspaper of Harrisonburg, Virginia]

© 2025 Marlene A. Condon All Rights Reserved

French

philosopher Henri Bergson is quoted as saying, “The eye sees only what the mind

is prepared to comprehend.” In the case of “invasive” plants, most people’s

minds are prepared only to see useless alien plants pushing out native plants

and posing a threat to us and our native wildlife.

In

other words, having been repeatedly exposed to the misleading invasive-plant

narrative recounted day after day on television news and public television

programs, as well as in newspaper and magazine articles, people see what

they’ve been told to see. But what they think they see is not reality. It’s the

mis- and even dis-information with which their minds have been filled.

Herewith,

truisms regarding the wildlife value of so-called invasive plants that only the

unbiased eye can see.

Autumn Olive (Elaeagnus umbellata) This Asian shrub is the most valuable plant for

wildlife usage I’ve ever documented, yet it is, perhaps, the most hated of

“invasive” plants. Because it’s easily seen filling in old farm fields and

highway medians, usually alongside the native Eastern Redcedar (Juniperus

virginiana)—once also despised by farmers—it appears to be overly numerous.

Yet we should be thankful for

this plant. Like the redcedar, it’s a colonizer working to refurbish degraded

soil that has been compacted by cows or bulldozers and is nutrient-poor due to

loss of topsoil—conditions most native plants find difficult or impossible to

grow in. But unlike the native juniper, Autumn Olive feeds a huge variety of

wildlife with its buds, blooms, fruits, and even its leaves, thus dispensing

vital nutrition throughout the year. By increasing the diversity of plant life

in degraded areas, Autumn Olive increases the diversity of wildlife as well.

Burning Bush (Euonymus alatus). Almost equal in value to

the Autumn Olive, this Asian shrub also provides a cornucopia of food in the

form of buds, blooms, fruits, and stems for an array of wildlife, in addition

to nesting sites for birds.

English Ivy(Hedera helix L.) Brought here by early European colonists, English Ivy is a superb vine for assisting pollinators and birds in disrupted soils (old homesteads and more-recent development). It makes flowers in fall when many blooming plants are petering out, and the resulting blue fruits persist into winter. A plant that spreads mainly by

vegetative growth, it’s typically found only where people dwelled long ago or more

currently, having been deliberately planted by them.

|

| The interestingly shaped fruits of English Ivy (Hedera helix L.) near the end of December help to feed local and migratory birds at the edge of a restaurant’s parking lot in Charlottesville. |

Japanese Honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica) Once disparaged as much as

Autumn Olive is now, this vine is a wonderful wildlife plant. In this time of

climate change, especially, nonnative plants are much more reliable in their

habits and can be counted on to assist animals that come out of hibernation or

migrate back too early to receive sustenance from still-dormant native plants.

Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, in particular, benefit from its early blooms loaded

with nectar upon its return to our area in April.

Bradford Pear (Pyrus calleryana) Native to East Asia and spreading for the same reasons other “invasive” plants move away from their original locations, this species grows profusely in the disrupted soils of retired farmland and disturbed areas of old and new developments. The multitude of trees in limited areas— eye-catching in spring due to the white flowers conspicuously covering every bough— draws attention to their presence. Only because these wildlife-friendly trees are nonnative do folks complain about them, but they shouldn’t. In this time of pollinators struggling to survive, Bradford Pears are a lifeline, supplying a large supply of nectar for bees and numerous other kinds of insects. The fruits are especially important to wintering birds.

|

| A blooming Bradford Pear (Pyrus calleryana) stands alone in a sea of native trees, the only woody plant able to feed native pollinators flying on a March day. |

Royal Paulownia (Paulownia tomentosa) Originating in Eastern

Asia, this large tree was admired just a few decades ago for its unusually

large purple flowers that opened in spring. But with the big push for only

native plants to occupy the landscape, people have been cutting down these unique

trees. What’s left are empty spaces unable to provide the wealth of food the

Paulownias once did. The huge foxglove-shaped blooms hold an abundance of

nectar for pollinators and transform into pods of tiny seeds beloved by

finches, especially the American Goldfinch and the Purple Finch from farther

north.

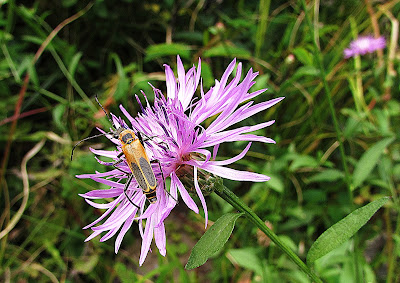

Black Knapweed (Centaurea nigra)

A lovely herbaceous plant that blooms well into fall, even during severe

droughts, this invaluable plant is targeted for removal by folks who are

against nonnative plants and ignorant of their great worth to wildlife. Black

Knapweed is one of the few plants our overabundance of deer refrain from

eating, even when food is scarce. Without this species of knapweed growing in

my yard in 2024, bees, beetles, and butterflies would have died, especially

those still active in late fall as the heat of summer endured into fall.

|

| A Pennsylvania Leatherwing beetle (Chauliognathus pennsylvanicus) finds nourishment on a Black Knapweed (Centaurea nigra) bloom in September in the author’s yard. |

Common Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) Once considered the scourge of lawns, this small, yellow-blooming herbaceous plant has practically disappeared from towns and subdivisions, thanks to pesticides. They might be lost in rural areas, too, as people have become obsessed with manicuring (sanitizing) the environment. But it should be noted that they feed pollinators, sometimes even on warm winter days when nothing else is blooming and insects are active.

People need to recognize

the significant roles “invasive” plants play in our environment.

NATURE ADVICE:

All

“invasive” plants provide one or more of the following environmental services:

· Holding soil along

degraded waterways (think Japanese Knotweed) and on steep, barren slopes in

yards (e.g., English Ivy)

· Enriching

nutrient-poor soil with nitrogen by way of nitrogen-fixing roots (e.g., Autumn

Olive) and/or decomposition of the plant after it, or sections of it, dies

· If evergreen, furnishing

shelter in winter where wildlife can sleep and/or roost (e.g., Japanese

Honeysuckle)

· In summer, supplying

nesting sites (e.g., Japanese Barberry) for some kinds of birds and a place for

some kinds of insects to lay eggs (e.g., Royal Paulownia)

· Feeding

pollinators with nectar-filled blooms (e.g., Burning Bush)

· Feeding birds and/or

mammals with fruits, buds, seeds, and/or leaves (e.g., Ailanthus)

· During drought, making drinking water and/or sap available to birds and insects by guttation (e.g., bamboo).

|

| A pair of goldfinches visit a small bamboo (subfamily Bambusoideae) stem in the author’s yard to obtain water and/or sap. |

DISCLAIMER:

Ads appearing at the end of e-mail blog-post notifications are posted by follow.it as recompense for granting free usage of their software at the author's blog site. The author of this blog has no say in what ads are posted and receives no monetary compensation other than the use of the software.

No comments:

Post a Comment